|

home

advanced |

Creating

the "Berkovian" Aesthetic Chapter III Performance Philosophy and Practice Though uniquely his own, Berkoff's production style descends from the tradition of presentational directors This heritage rejected twentieth century realism, choosing blatant theatricality over subtle nuance. Such directors bridged the divide between modernism and what was to become post-modernism, evolving into, what Annette Lust calls post-modern mime. She cites Berkoff's mentor Jaques Le Coq as key to this development and describes chief characteristics of "post-modern mime" in her book From Greek Mimes to Marcel Marceau and Beyond (2000). Lust describes sixteen specific traits; Berkoff's work fits every one of her descriptions, including There is a recycling or new use of existing forms no longer regarded as separate arts. For example, the frequent crossbreeding with other art forms -- such as dance, music, performance art, circus, puppetry, film, and pictorial art -- creates an artistic pluralism that is not necessarily integrated but offers a new vitality.(111) In 1973, Berkoff and The London Theatre Group declared their own mission statement, which places them within Lust's parameters:

The philosophical content included in this mission statement has remained constant in Berkoff's subsequent career; mime, stylized movement, exaggerated vocal work, direct address, asides, and improvisation are fundamental elements of Berkovian acting, and are components of practically every Berkoff production. Berkoff expects actors to willingly sacrifice themselves physically and emotionally, ready to perform whatever tasks are necessary to illuminate the text. In his quest for vitality, Berkoff creates and breaks theatrical conventions, resulting in a style composed of contradictions. These contradictions are rooted in his determination “to see how I could bring mime together with the spoken word as its opposite partner, creating the form and structure of the piece” (53). This characteristic can be traced to his training Free Association with Le Coq, whom Thomas Leabhart, author of And Post-Modern Mime (1989), acknowledges as Modern teaching "mime to talk" (101). To fuse opposites, Berkoff relies on mime, a traditionally silent form, yet he cherishes the spoken word; his productions are over-the-top in energy level yet depend on great subtlety; the actor must never appear self-conscious yet his presentational style is very self-conscious; and Berkoff meticulously choreographs movement yet he encourages improvisation. Berkoff outlined his philosophy thoroughly in “Three Theatre Manifestos” (1978) which, according to him, has not changed significantly through the years (Personal interview); he summarized his theories by stating: “In the end there is only the actor, his body, mind and voice.” He continues, “The actor exists without the play . . . he can improvise, be silent, mime, make sounds and be a witness” (11).Gambit The aural environment of the plays, an outgrowth of the performer, should be created vocally and physically. Berkoff explains:

By asking the actors to create sounds, Berkoff breaks with traditional mime convention. Like many of Le Coq's students, Berkoff freely bastardizes the pure form of mime to create an individualized style: the Berkovian. Le Coq encourages this practice, believing "it is important to be open and not to copy the style of someone else because you will never be as good as he is. Each is better in his own style" (quoted in Lust 106).

speaking as possibly his greatest fan here, I believe Berkoff is often given too much credit for "originating" an individual performance style and an ensemble approach which is 90% derivative of Le Coq and thus actually has firm roots in Commedia delle Arte. [Ref 3-4] As a performer, Berkoff's own mannerisms give the general style a specific personality, but this is not the same as saying the whole style is Berkovian, or that to perform in the same style one needs to assume the same mannerisms. (6 October 2000) In Modern and Post-Modern Mime, Thomas Leabhart summarizes Le Coq's pedagogical influence: Lecoq's [Ref 3-5] school is one of those theatres that, rather than being a résumé of what has happened, has helped young performers find new directions and so revitalize the theatre. Lecoq's whole vision of the theatre is like Copeau's, remain on the fringes of the commercial theatre, not wanting to give themselves to it as it exists. They, like their teacher, work apart, preserve their artistic vision, nurture their strength, and steadily increase their power to influence the course of theatre history. (101-102) [Ref 3-6] Like Lust's definition of postmodern mime, Leabhart's summary of Le Coq's influence is applicable to Berkoff. Berkoff’s first production, an adaptation of Franz Kafka's short story In the Penal Colony (1967), addresses human brutality, lust, vengeance, and cruelty. In it a prison officer explains to a visitor, with perverse passion, the workings of a machine called "the harrow" -- its sole purpose: to torture prisoners. In his introduction, Berkoff explains that the story is "a strange tale of torture and suffering. The Officer wishes to preserve his way of life and the punishments that were a 'feature' of the Colony and which attracted in the past such avid response" (Trial 123). This early Berkoff adaptation is quite literal because he faithfully turned Kafka's words into dialogue. Although the seed of the Berkovian performance style had already been planted, Berkoff did not think to create the harrow through mime. Instead, he had a machine built for the actors to refer to and react against. Berkoff later noted: “Someone suggested that it [the harrow] should be a plain block and one should merely describe it and mime its function. I daresay this could work and enable the actor being tortured to express the pain [. . . .] (Free Association 294). This machine, though built to look "real," should not be confused with an attempt at realism as his cohesive aesthetic for Penal Colony. In another Berkoff paradox, the one literal element in this production is also the one Kafka completely invented, a tribute to Kafka's own theatricality. In 1999, Berkoff wrote an article for The Independent chronicling the thirtieth anniversary of the first production of Metamorphosis. In it, he freely admits travelling to Oxford to see a different student adaptation of Metamorphosis, directed by John Abulafia, providing inspiration toward creating his own performance of Gregor:

Berkoff wanted his own Gregor to remain completely on-stage through the entire performance, so he expanded the Oxford idea to encompass his entire body. Berkoff explains how he developed his concept for performing Gregor:

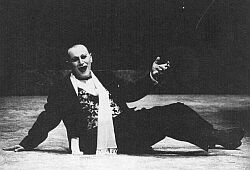

The actors in the subsequent productions of Metamorphosis have not altered Berkoff's original physical interpretation. This is a very different image than an actor on "all fours"; when the Gregor beetle moves, the actor uses his fingertips, forearms, elbows, knees, shins, and feet in order to stay as close to the ground as possible. Through this technique, the smallest movement assumes significance, because the physical interpretation is all inclusive. The actor abstracts Gregor's voice, using echo effects and grotesque sounds when he is speaking to his family. The speech is easier to interpret when he speaks interior monologues. Gregor will hiss, yell, and whisper -- taking full advantage of his vocal range as he must of his physical arsenal. [Ref 3-7] Everything is suggestive, never literal. In Berkoff's published adaptation of Metamorphosis (1981), he provides interpretation and blocking notes. The following section illustrates Berkoff's written stage directions and dialogue, along with my running description of the actual scene as produced in the 1987 production starring Mikhail Baryshnikov at Duke University. BERKOFF'S STAGE DIRECTIONS: Image -- the listless automatic waving [of Mrs. Samsa and Gregor's sister, Greta] as FATHER leaves and a strong light revealing the swaying huge body of the GREGOR beetle -- the anticipation of horror. By this time GREGOR has climbed on to the ceiling of his cage and just hangs there. MOTHER and GRETA are waving goodbye to FATHER. GREGOR speaks, rocking in time to the waves [of music]. (This speech is a grim foreshadowing of events and the separation of animal from human. The acceptance of his state which now almost gives him pleasure. Hang your legs over the cross bar and cup your toes into the side bars to give your body a braced, arched look.) (107) DESCRIPTION: Cyclorama is lit with intense blue light. MOTHER and GRETA are on either side of the jungle-gym like structure in black silhouette, waving in slow-motion. Gregor is hanging up-side down from the top of the "set" in white spotlight. Music underscores, sounding like synthesized strings; it is warped yet hypnotic and soothing.

Music ends as the next dialogue begins. White light dims on GREGOR leaving him, MOTHER, and GRETA in silhouette against the blue cyclorama This technical description is important, yet, it is how Berkoff integrated his portrayal into the production as a whole that made it successful: “The geometric shape of the insect governed my movements, for not only must one find the animal, but the animal is the mise en scène, the production” [Berkoff’s emphasis] (Trial 72). Later in the introduction to the published text of Metamorphosis, Berkoff expounded:

Berkoff continuously echoed this form in the acting, set, movement, and lighting. [Ref 3-8] This form encompassed the content.

The environment was also reinforced by him remaining on-stage throughout the entire production, projecting a looming presence, as if peering through the bars of the cage. This presence was emphasized by extensive use of light and shadow. Berkoff integrated the other actors into the mise-en-scène by, at times, creating “animated marionettes that moved, reflecting the insect’s movements, so that they as a group, more than Gregor, were the dung beetle in reality” (72). Berkoff decided that mime, stylized movement, and tableau were the most effective means to create living marionettes and created a rhythmic motion for the family. At times, the actors spoke in stylized speech patterns, accompanied by a metronome, and, at others, spoke with natural voices; this created a striking juxtaposition between what is mechanical and natural. Berkoff's choices became distracting, and, even irritating to some critics. In his 1989 review of Metamorphosis for The Washington Post, David Richards complains that Berkoff directed the play in an outsized, caricatural manner. Indeed, at times they all carry on like the animated figures that pop out, hourly, from a cuckoo clock. But they are just as apt to indulge in the histrionic flourishes of the 19th century tear-jerker. Nearly every gesture, line and pose, grandiose or otherwise, is accompanied by a sound effect or a lighting effect. Sometimes by both. ("Baryshnikov's Bare Feat" D1) Richards' criticism is consistent with Lust's description of post-modern mime: "The form might represent a collage of mixed and superimposed genres -- stylized and non-stylized, romantic, realistic, baroque, mythological, ornamental, decorative, and ritualistic -- sometimes employed beyond the point of excess" (111). There is an irony that Berkoff, who abhors the clutter of the realistic stage, is accused of too much business. Again, Berkoff’s theatre is not meant to have a verbal focus nor a realistic aesthetic, but when he goes to such extremes to stylize a production, he often over-burdens the work. While Berkoff has often been accused of excess, such criticism of Metamorphosis is not completely representative. Unquestionably, Metamorphosis must be considered a success, considering its longevity and popularity amongst fans and artists alike. In 1978, Bruce Elder summarized what he considered the success of Metamorphosis: It is an ideal vehicle for Berkoff’s talents. He always seems to relish the psychological parable and Metamorphosis, with its resonances of human cruelty, of prejudice, of familial cruelty and intensity stretches his imaginative powers to the limit. To see Terry McGinty as the man beetle is to marvel at the brilliance of Berkoff’s methodology -- no props, no costume, no special makeup. Just a man being a beetle. So totally convincing is the portrayal that the surrealistic notion of a man-beetle melts, like a Dali landscape, into a horrifying reality. (40) Elder’s characterization of Berkoff’s acting style is right on target. For all of his complaints against naturalism, Berkoff aims to simply “be” the character. Berkovian acting, at its best, is acting with a "wink and a nod," or as Lust describes much of the Le Coq influenced, movement-theatre: "a parody of itself" (111). This convention establishes a transparency so the audience can see through the character to the actor. Hopefully, both audiences and actor always remain conscious of this process. Berkoff is aware that one can “go over the top and be an embarrassment.” However, he also believes that an actor will be successful “with a little conviction and not a little bravery” (I am Hamlet 62). Critics rightly argued, for example, that Kafka’s stories, though expressionist in content, are written in a realistic style which Berkoff distorted with his own abstract mise-en-scène. Of Berkoff’s 1991 production of Kafka's The Trial, The Independent’s Peter Kemp grumbled: Where Kafka’s effects are underplayed and low-key, Berkoff’s are always overplayed and strident. Kafka’s settings are ramshackle warrens of oddly-shaped, cluttered little rooms, ill-lit, murky, hemmed in by fog or smoky gloom. What you see on the Lyttelton stage, on the other hand, are wide expanses of open space and characters bathed in glaring light. Where Kafka always keeps outlandishness within the bonds of ostensible ordinariness, Berkoff quickly slips the leash. His characters mug and pantomime through routines borrowed from Expressionist cinema, circus or music hall. They have seizures of hyena hysterics or St. Vitus convulsions, bloat into dropsical hulks who splutter their lungs out or give vent to Force 10 fits of farting. ("Guilty" 15) Benedict Nightingale of The Times concurs, writing that the 1991 production of The Trial may please those who like vaudeville effects and value theatrical invention for its own sake. But does it altogether serve Kafka? There were times last night when I for one wondered if I was caught up less in Joseph’s grim emotional journey, more in Berkoff’s bravura imagination. ("A Journey Going Nowhere" 22) Berkoff has heard these charges that his style is heavy-handed, and defended his approach in Free Association:

He readily acknowledges that, as a director, he does not set out to produce literal reproductions of texts on-stage. Berkoff rarely relies solely on the author’s intent, preferring to use the text to communicate his own ideas. He is honest about this approach, calling his staging of Hamlet (1979): “a dissection of the play” (I am Hamlet vii), and explaining of Agamemnon (1973) that he “attempted an analysis of the play rather than a realistic rendering” (Agamemnon 7). It should be noted that Berkoff will liberally cut texts, including Hamlet and Coriolanus. Agamemnon was unique for Berkoff as it was an adaptation of a play as opposed to a novel -- a technique he also used for Miss Julie versus Expressionism. Agamemnon's style is the type of blunt writing more closely associated with his later, original plays. Berkoff began Agamemnon with a prologue, the "Legend of the Curse":

Remaining within the context of the larger cast productions like The Trial and Agamemnon, Berkoff continues the trend of actors creating the environment within the non-realistic sets in Hamlet (1979).This forced the omnipresent cast of ten to create Elsinore in total. He employed a few small, literal props, like fencing gloves for Hamlet and Laertes to wear while miming the final duel. In I am Hamlet (1989), [Ref 3-10] a journal that chronicles his production of Hamlet, Berkoff described the staging virtually line by line and took great pains to explain how the actors created the environment:

Berkoff co-opted Brecht's concept of witnesses by keeping the performers on-stage throughout the entire production, and attached it to the movement-oriented theatre specifically inspired by Barrault and Le Coq. For a short time thereafter, Berkoff worked with original texts with smaller casts and less stage movement. In Greek (1980), he started “honing things down to a minimum until the bare essence remained,” continuing to do so in Decadence (1981), “where movement was reduced to two people on a sofa” (Free Association 344). In the two actor play Decadence, each performer plays two characters -- one upper-class (Helen and Steve), and one middle-class (Sybil and Les). Steve is actually married to Sybil but involved with Helen; Sybil is involved in an affair with Les, who is spying on Steve. Berkoff creates magnificent, decadent images of feasts, parties, and sex -- each more extravagant than the one before it:

When performing this scene, Berkoff exaggerates an upper-class, nasal voice while actively describing the feast. He mimes the meal by "pouring" the wine with a vocal effect; greedily cutting his steak; and tossing mushrooms into the air -- swallowing them with a gulp. Beyond creating the feast, Berkoff briefly assumes the role of Giovanni.On Blow Your Mind, Berkoff describes exactly how he established the character:

Through Berkoff's physical-theatre, he creates this scene without props, leaving the set minimalist (performed on a sofa), while paradoxically, creating the image of a cluttered dining table. Greek [Ref 3-11] is a radical retelling of Sophocles' Oedipus Rex. Berkoff set his version in the modern-day East End, amongst the plague of poverty. Greek's story only parallels certain elements of the original and differs greatly at the climax through the denouement; Berkoff's protagonist, Eddy, continues his relationship with his mother. Although the script for Greek was not well-received, most critics raved about the staging. Of the 1980 production of Greek in London, Leigh Caldicott of Plays and Players wrote: As a director, however, Berkoff is unparalleled [. . . .] The rhythmic choric sequences around the family table, on the tube or in the airport represent Berkoff's writing and staging at its best, and are executed with consummate precision by the cast. Everything is conjured up from nothing in front of our eyes. (24) Martin Hoyle of The Financial Times concurred in his review of the 1988 London revival: "About Berkoff the director there are no doubts. This superbly drilled production at the Wyndham's imposes its own dark world by sheer bulldozer conviction" (21). Welton Jones of The San Diego Union-Tribune panned the 1984 American tour production in San Diego (which premiered in Los Angeles), but gave modest praise to Berkoff's staging: "Some of Berkoff's techniques are noteworthy, though few are original. He borrows cleverly from the abstract theatre of the 1960s, the British music-hall tradition, the post-modern technocrats and the performance art tricksters" (E5). Though panned by the critics, Berkoff is proud of Greek because, he believes, it satisfied his "mandate" to himself, "that nothing I do should resemble anything I have done before" (Free Association 3). An issue arises for the audience member who sees multiple Berkoff productions. Because Berkoff often creates "types," there is a tendency for certain character types to be portrayed in the same manner, regardless of the production. Shakespeare's Villains (1998) is a microcosm of this trend. Berkoff explores the "villain" as an archetype in, what he subtitled, a "Masterclass in Evil." Some critics found Berkoff's portrayals redundant. In his 1999 review for the Los Angeles Times, Michael Phillips remarked: The downside to his approach becomes apparent midway through Shakespeare's Villains. In Berkoff's gleefully outsize characterizations, everyone come off like a variation of the same all-purpose weasel [. . . .] (F1) This fault, which is easily noticed in the context of Villain, is also noticeable in the larger framework of Berkoff's career. This is not only true of watching Berkoff as actor on-stage -- it also holds true for those he has only directed. In Meditations on Metamorphosis, Berkoff rails at The New York Time’s Frank Rich [Ref 3-12] for his criticism of the 1989 revival of Metamorphosis: The most banal statement of all time and what for me relegated Mr. Rich’s mind to the garbage heap of history, the dustbin of redundant journalism, was the review of the fine actor René Auberjonois in which his performance [of Mr. Samsa] was compared to my performance as Hitler in War and Remembrance (incidentally highly praised), as if I had chosen to model René’s rôle on mine as Hitler!! And the junky critic seized on this performance to clout my actor. I had directed René as a bullying, oppressive father who eventually tries to kill his own son, but the raging had a certain satiric edge -- he was more a bullying buffoon, though his rages were also meant to terrify. [Berkoff’s emphasis] (128) Consistently, Berkoff’s fathers are blustery, boorish, and racist; and, his mothers are nurturing and caring, but disillusioned -- no doubt a reflection of Berkoff’s home life. In addition to all of the productions of Metamorphosis, this is especially true in his early plays East, West, and Greek. Berkoff gears his productions toward “truthfulness,” and accepts that during each performance the actor, and the audience, may experience a different “truth.” He has been known to make dramatic changes during a performance when impulse strikes, and encourages this behavior in other actors. East contains one of Berkoff's most graphic speeches, "Mike's C*nt Speech," which, in turn, caused Berkoff to gradually develop his performance:

In Free Association, Berkoff explains how he, out of fear, developed, and improvised, his schtick for “Mike’s C*nt Speech” in East:

Berkoff the writer proves a bit bolder than Berkoff the performer. The vivid language in his plays demands the over-sized performances necessary to successfully produce a Berkoff script -- this is even true for Berkoff as actor. A complicated element of Berkoff’s aesthetic lies in his relationship to language. In 1995, on the television program Blow Your Mind, Berkoff explained "as we see the physicality of the player, there is a physicality of language." Being a playwright, words are obviously an important commodity, but he usually finds the language of the body to be even more communicative. In Contemporary Theatre Review (1996), Nicole Boireau quotes Berkoff saying, “My theatre is verbal” (82), yet in 1991, Berkoff also told The Times' Kenneth Rea, “The act of theatre is the act of a gesture. The gesture comes first, the sound comes second and then they marry in equal harmony” (Features n. pag.). In a 1992 interview with William Cook of Midweek, Berkoff complains, “Other productions are so verbal -- they don’t lend themselves to any imaginative expression of the body” ("Muse" 10). The key to this Berkovian conundrum is his ability to bind words to gestures. Language becomes action as opposed to substituting for action. At times he pushes a stylized script to the border of comprehension through a stilted delivery. Berkoff's technique is uniquely his own, yet also falls in line with contemporary theatre practice:

The Berkovian speech pattern, like most elements of his productions, has its great admirers and detractors. Berkoff’s 1994 production of Richard II garnered two separate reviews from The New York Times, which are as strikingly contrasting as possible. In his scathing review, David Richards wrote: Just as assiduously [as the movement], Mr. Berkoff breaks up normal speech patterns. Words are purposefully overarticulated, extended to twice their normal length (“physician” in the king’s mouth becomes “phee-ZEE-see-en) or subjected to swooping rhythms of a speeding roller coaster. ("Director's Stylized" C:1) Of the same production, Vincent Camby felt: The best thing about this production is its consistency of language and performance. The London-born Mr. Berkoff has successfully staged an American Shakespearean production in which all of the actors sound as if they were born on the same continent, even if they weren’t, and in the same century. There are no great oratorical flourishes, but there are also no battles of American, English and drama-school accents and speech patterns. (2:5) Beyond making the language comprehensible, Camby noted how Michael Stuhlbarg’s (who played Richard II) speech patterns separated the king from the rest of the cast: “There’s something a little too precise about his diction, as if everyone else had yet to master the proper way of speaking. His manners are polite to the point of sarcasm” (2:5). This was a character choice and not an inconsistency in the production.

This commitment to language seems contradictory to Berkoff’s complaints about verbal theatre. Berkoff circumvents any contradictions by stylizing the language to such an extreme that a new form emerges. In the case of Salomé, Berkoff married his speech pattern to the movement until the entire production was presented in slow motion; the finished production ran 2 1/2 hours -- with no intermission. In his introduction to Lord Alfred Douglas' translation of Salomé (which was published by Faber and Faber to coincide with Berkoff's production at the Royal National Theatre), Berkoff explains, "I decided the weight of Wilde's language had to be carried slowly as if it were a fragile and precious cargo capable of being shattered by anything less than the most careful handling. So I decided to try fusing this movement to the text." Berkoff continues to explain that "the bonding was music, played delicately on a piano" (xii). In his review of Salomé for The Daily Telegraph, Charles Spencer wrote, “their vocal delivery is equally sluggish [as the movement]; every vowel, every consonant is savoured, so that a single sentence seems to last from here to eternity” (“Wilde Gestures” n. pag.). This view is compatible with Richards' review of Richard II and demonstrates a consistency in Berkoff's aesthetic use of language. The manipulation of sound through language is a central element of Berkoff's acting style, but so is the creation of sound effects. Actors might create literal sounds like missiles exploding, or, environmental sound effects like winds blowing through trees. Sound is an essential detail of the environment and, typically, Berkoff prefers to let the performers organically create the effects. Early in his career he found the idea of creating sound effects through the actors exhilarating, but later, Berkoff found the process tedious. Of his 1991 production of Coriolanus in Münich, Berkoff complains:

These abstract sounds compliment the mime, and is a characteristic that distances Berkoff, and his contemporaries, from traditional mime. According to Berkoff:

Lust explains that this technique is typical of artists who descend from the Barrault and Le Coq tradition: Exchanges between mime and verbal theatre are frequent. While postmodern verbal theatre might contain more movement than, for example, the verbal theatre of the 1950s, postmodern mime also incorporates a broader range of physical and verbal expression, including movement for the actors and the use of props and voice. If voice is incorporated, it is not done so traditionally and might consist of only vocal sound or broken dialogue. (22) Much has been made of Berkoff’s use of verse in his playwriting. Berkoff assists an actor in establishing a character’s class, psychological state, and physicality through the rhythm of the written text. He aims to desensitize an audience to prejudices regarding class and gender by elevating even working-class language to the poetic. In the East End plays (East, West, and Greek), Berkoff juxtaposes disconcerting images of East End, working class life with classical allusions and blank verse. His language is so vivid and active that it demands the actors to match the words with exaggerated physical gestures. Berkoff paints pictures, reducing the need for visual elements because the words help the actor to create the environment. Although the form is poetic, the content might be vulgar. This technique was well-received in East (1977), considered by many critics as original and effective. In The Spectator, Ted Whitehead's comments sum up most of the critical reaction to the 1977 production of East: Berkoff transforms the ugliness of his material by his presentation: the language is an ironic mix of Shakespearean phrases and East End argot, the style ranges through song, dance, mime and dramatic confrontation. "It is meant to be a frontal assault," says the programme; it is and it's superb theatre. (n. pag.) By the time Berkoff directed and performed in the British 1988 revival of Greek, many critics had grown tired of this technique. Martin Hoyle of the Financial Times complained that "Berkoff the writer poses certain problems. His style ranges from conventional and by now unremarkable mock-Shakespearean pentameters to lyrical obscenity [. . . .]" (21). As early as the original 1980 production of Greek in London, these complaints had begun. Leonie Caldicott of Plays and Players complained: Lavatorial images drop like -- well, drop abundantly from his pen. Some of these are apposite and very funny. But they lose their impact through over-use. A turd is a turd is a turd. 24) Caldicott, however, also recognizes that Berkoff not only uses language to shock but also uses it as an active substitution for physicality: A clue to a source of Berkoff's verbal methodology lies in the power Greek attaches to words. Through them the Sphinx is defeated, and through them Eddy kills his father, in an exchange where verbal missals take the place of physical blows. This is not a vision based on dialogue, but on the power of personal articulation. (24) Ironically, Greek contains one Berkoff's most gentle passages, though it was overlooked by critics:

BERKOFF'S STAGE DIRECTIONS: [Ref 3-14] The stage is bare but for five chairs in a line upstage whereby the cast act as a chorus for the events that are spoken, mimed and acted. A piano just offstage creates mood, adds tension and introduces themes. A large screen upstage centre has projected on it a series of real East End images, commenting and reminding us of the world just outside the stage. The cast enter and sit on five chairs facing front -- piano starts up and they sing "My Old Man Follows the Van" -- out of order and in canons and descants. It comes suddenly to a stop, MIKE and LES cross to two oblong spots -- images of two prisoners photographed for the criminal hall of fame. They pose three times before speaking. DESCRIPTION: Proscenium Stage. Five stools set upstage from right to left. Backdrop of faded signs indicating East End business and locations. PRE-SHOW MUSIC: Piano underscoring reminiscent of 1880s melodrama, 1920s vaudeville, and music-hall tunes. LIGHTING: Black out. Actors appear on-stage seated, stage right to left: Les, Dad, Sylv, Mum, and Mike -- Mum is played by a man. [Ref 3-15] Actors are lit in half-shadow. COSTUMES: LES AND MIKE: Black blazers with high, pointed, lapels; suit vest; blue-jeans; neck-ties; crew neck tee-shirt (MIKE's is white; Les's is black); work boots. Ultimately, a punk-rock parody of the working class attire of the previous generation DAD: A cover-all work-suit with kerchief around his neck. SYLV: Tight fitting, red, sleeveless top; short black skirt; garters and black hose; high heels. MUM: Floral scarf around hair; mismatching, drab, tattered, floral apron over house dress; tan hose; house slippers. OPENING ACTION: The sequence begins in stillness, with piano underscoring. LES begins singing My Old Man off-key, in a heavy Cockney accent. Other characters join in, one-by-one, at different portions, off-key, overlapping until it is a jumble of sounds and words. SYLV is the last to join in, singing, "Daisy, Daisy" (Bicycle Built for Two). The actors remain seated, but are very animated as they begin improvised dialogue and mimed motions indicating that they are in a pub. The music transitions into an upbeat music-hall melody. The opening sequence ends with MUM saying: "Quite a nice change to go out again." [Ref 3-16] All of the dialogue is spoken in very heavy cockney accents; the above sequence takes ninety seconds. MUSIC changes into the villainous underscoring of a nineteenth-century melodrama as MIKE and LES walk downstage into individual pools of light and strike poses. LES is stage right; MIKE is stage left. Upstage, MUM, DAD, and SYLV freeze on their chairs.

The actors continue in this manner throughout the first scene, as Mike explains the reason for his fight with Les:

This faux Shakespearean verse elevates the triviality of the circumstances to epic proportions. Berkoff follows the opening scene, with scene two -- what he describes as a "Silent Film Sequence." A silent film now ensues performed in the staccato, jerky motion of an old silent movie. It shows MIKE calling on SYLV -- meeting MUM and DAD -- going for a night out -- SYLV is attracted to LES -- a mock fight. They are separated and SYLV's long monologue [scene three] comes from it. The movie sequence reinforces and fills in the events of scene I. (11) The following description more accurately details the action in the 1999 production: The entire stage is lit. MIKE and LES quickly remove their blazers which they toss offstage. MUM, DAD, and SYLV move downstage as piano underscores the scene in a fast-paced sequence. MUM and SYLV move downstage right and mime SYLV's preparation for the date -- there are no props in the entire scene. MUM "combs" SYLV's hair while DAD is downstage left "drinking" a cup of tea. All of this action is fast-paced and rhythmic. MIKE arrives and knocks on a door (tapping his foot on the stage to make the "knock" sound); LES is waiting with his hands folded upstage right. DAD opens the door and he and MIKE mechanically shake hands, then repeat the motion several times, moving in reverse and forward again -- Mike smiling at DAD while DAD suspiciously sizes up MIKE. SYLV finishes dressing (mimed) and MUM moves toward the door. SYLV glides over to MIKE, who is still standing with DAD, and plants a kiss on MIKE's cheek. DAD again sizes MIKE up as MIKE kisses MUM's hands. The sequence is "rewound" and repeated a few times. MIKE spits toward the audience after each kiss as MUM, blushing, indicates her approval of MIKE (not seeing him spit). SYLV and MIKE make their way toward the door, repeatedly waving goodnight to the parents. MIKE and SYLV "exit" the room to musical underscoring by the off-stage piano, while MUM and DAD wave mechanically. MIKE and SYLV mount an imaginary motorbike and put on helmets. During a five second sequence, MIKE and SYLV, simultaneously, move their head toward the side three times, while making "swoosh" sounds, as if they were speeding down the road watching the sights as the soar by. MIKE and SYLV arrive at their destination -- a pub -- and enter together. MUM and DAD transform into people standing at the pub, repetitively drinking and toasting in a large mimed-action. MIKE and SYLV make their way to the "bar" and the four of them drink their beer (out of imaginary large mugs), all syncopated to music. LES quickly enters from upstage, through an imaginary door and immediately makes his way next to SYLV -- MIKE does not notice this. LES "chats up" SYLV who begins to provocatively shake her body and lean towards him. LES lowers his posture until he is "talking" to SYLV's chest. MIKE notices this exchange and the two (MIKE and LES) shove each other -- with SYLV in between them. Sylv ducks and the actors playing MUM and DAD restrain the two in a repeated motion -- the lads lunge forward and are then pulled back. During the drinking and fight, the characters have made grunting "oink" sounds to the beat. They continue the rhythm of the battle until everyone makes their way upstage to their chairs except SYLV, who remains downstage to begin a monologue which begins scene three. Once again, the pace is rather quick in that scene two is performed in approximately four minutes. Scene three is a direct address monologue, by Sylv, in which she, too, describes the fight. In the first three scenes, the actors communicate the story in three different ways: through dialogue, mime, and as a chorus when not directly involved in the scene. In 1999, John Peter of the Sunday Times, commented on the importance of language to complement the action in East: As in all Berkoff's best work, the words and the visuals are inseparable. When Mike and Les (Christopher Middleton, Matthew Cullum) do their Harley-Davidson sketch, their brilliant miming of man and bike and their brutally inane descriptions of macho pleasure work together to give you a vision of grotesque pseudosexual satisfaction. Mime and words, on their own, would not be enough; together they are a piece of obscene reality observed from without and within. (Features n. pag.) Berkoff mixes the order of the scenes, sometimes relying on mime, sometimes language, and other times a mixture of the two. Berkoff traces the power of language to his youth, understanding that well-chosen words can have destructive power. In a 1991 interview in The Financial Times, Berkoff reminisces: "I remember older chaps who were very articulate and very funny. They’d use all kinds of verbal monstrosities to express things; even make up their own language. You could be demolished with words, and you had to fight back with words" [Berkoff’s emphasis] (N. author. Interview 5:3). Again, his emphasis on words is as strong as that of the physical gesture. While the abstraction of movement, voice, and sound should be considered the grounding for an understanding of the Berkovian aesthetic, there is an exception to this rule. Acapulco (1990) is unique because of Berkoff’s prescribed performance style. Berkoff suggests that “The acting should be easy and casual broken up by laughter and the normal behavior patterns of people relaxing after work” (Collected Plays II 89). This naturalistic stage direction is unusual for Berkoff and stands out from his canon. As a playwright, part of Berkoff’s method is to tell stories in past-tense so the character describes what they have seen as opposed to seeing it for the first time. This is reminiscent of classical Greek drama, whose messengers illustrate what they witnessed off-stage. The idea of time is liquid for Berkoff, as in East, where time and period are ambiguous. Berkoff describes Les and Mike, the protagonists, as “lads” (30) and “boys” (37, 39) in the stage directions. Much of the play is told in flashback but the actors in the 1999 revival, Christopher Middleton and Matthew Cullum, appear no older than thirty. George Dillon “suspect[s] the current Mike, Les and Sylv weren't even born when the play was first put on” (www.east-productions.demon.uk). Nevertheless, Mike and Les describe dancing at the Lyceum, which Berkoff says is playing music of 1955. Berkoff was thirty-eight when he wrote and performed in East, which makes the actors age-appropriate during the original production. This revival, if primarily based in 1975, pushes the envelope of time by casting such relatively young actors. When the characters do step back and forth in time, as in scene eight when the parents take the family, portrayed as young children, to the seaside amusements, the passage of time is initially indicated by a lighting shift and a change in the musical underscoring. The music establishes the theme and mood of the scene, and helps to establish place. A mimed sequence by Mike, Les, and Sylv accompanies these shifts as they mime playing an assortment of children’s games. Dad’s initial line, “Years ago things were good” (21), occurs after the mimed transition, reinforcing the fact that another time and place has now been established. Dad continues with a short monologue placing the family at Kursaal Amusements, a seaside amusement park. Now a longer sequence begins with the entire cast riding a mimed carousel, the bumper cars, and finally a roller-coaster. The actors have become the set because a carousel has been constructed from human movement. Pace slows and quickens, accompanied by the live music -- slower, legato, motions on the carousel, and quicker staccato pace for the bumper cars. Les steps out of the group to take a photograph of the rest of the cast, with a mimed camera and next becomes an ice cream vendor. Les becomes separated from the cast, and as everyone else exits the scene, he is left on-stage to lament his situation in the "present." The musical theme changes and lights shift leaving a special on Les to begin the next scene. Time has moved forward as indicated by Les’s opening line, speaking in the past tense, “I was lonely” (21). The location is not yet specified, although toward the end of the scene, an absurd sequence acknowledges that the characters are in fact in a theatre and that time is relative to the world of the production:

At this point Mike and Les’s rapport is as punk-rock vaudevillians in what Berkoff calls “a kind of Beckettian oratorio” (Free Association 19). This Berkovian temporal phenomenon is evident throughout East. Berkoff the director has manipulated time in various ways throughout his career. In Kvetch, the characters often freeze in their place to suspend time while asides are delivered. In Berkoff’s production of Salomé, performed in slow motion in an attempt to emphasize the richness of the language, this technique created a decadent, indulgent environment. The Trial keys on the passage of time since it focuses on Joseph K’s eternal wait; and Actor, a one-man play, features an actor who "walks through his life watching it slowly disintegrate” (Collected Plays II 225). Berkoff’s disregard for linear time manifests in still other ways. He often disregards conventional age when casting actors -- himself playing Hamlet at the age of forty-two. This interpretation is not unprecedented though it did contribute to what Berkoff acknowledges, “the most awful battering from the press” (I am Hamlet ix). Similarly, Berkoff originally played Gregor Samsa when he was thirty-two years old, but later cast Mikhail Baryshnikov at age forty-one. In theory Berkoff’s demands on an actor are no different than that of Stanislavski: physical and vocal flexibility and a strong focus, but, Berkoff complains that because of Stanislavski and naturalism, theatre has “moved away from illumination to deception” (Gambit 12). For Berkoff the actor must be prepared to proceed beyond the physical and psychological into the spiritual. While revealing the text, the actor should also create some mysteries: “The ultimate aim is to bring the spectator into closer contact with the essential aspect of the theme -- to reveal it in all its mysteries -- and to be part of these mysteries” (8). Berkoff’s theory of acting can be partially traced to his infatuation with magic. Berkoff explains, “What we see is a series of problems being solved by the actor, and we like to watch this particular actor solving them, since he is more interesting than the event” (11). The actor magically conjures up a character, creating as much mystery in the conjuring as in the result. In a 1977 interview, Berkoff told Sheridan Morley of The Sunday Times of his confidence in his own ability to enchant an audience:

Berkoff searched for acting methodologies that allowed him to cast his spell, and inspired by Artaud, turned to alternative forms of literature. For Berkoff, like Artaud, theatre serves as a place for the actor, as well as the audience, to reach catharsis. On The South Bank Show, Berkoff stated:

He also took an Artaudian stance in “Three Theatre Manifestos”: “Be a sacrifice and live dangerously. What is vital to the spectator is your core, the inner part of you. As well as the words that symbolise the action” (Gambit 8). Berkoff learned to speak in a language of gestures as well as words. In “Manifestos,” Berkoff transitions from a pure Artaudian stance to include a more Brechtian philosophy of acting: All verbal communication is a form of acting. The telling of an event is to possess the event inside you. A person recalling an accident is acting out the event and filtered through prejudices [. . .] The actor is a witness for information he sees and the thoughts of the writer and he must filter them clearly through his observations. (Gambit 8-9) Berkoff’s declaration encompasses the intellectual (Brechtian) and spiritual (Artaudian) aspects of performance: “ACTING IS RELATED TO THINKING -- THINKING TO MOVING: one acts because one is moved to act; the event stimulates the response. All verbal communication is a form of acting. The telling of an event is to possess the event inside you” [Berkoff’s emphasis] (Gambit 8); Berkoff later distilled this concept into “All acting is quest for self anyway” (I am Hamlet 44). One should recognize that chronologically, Berkoff first was an actor, then playwright/adapter, and then director. In 1978, with that perspective intact, Berkoff bemoaned the plight of the actor: In being a witness for the writer’s imagination he [the actor] can be a tool, a puppet or part creator. He must of course share the responsibility. The two combined create an event, and usually the writer’s work is eulogized by the actor. If the actor is good, the works will be stronger, wittier, interpreted and pointed in the right direction, but if the actor is bad then of course the actor will suffer, no blame being attached to the writer, only sympathy. If the text is bad, the actor will still be blamed, since somehow he still appears to be the event. When the text is silent, the actor is still there on the stage. (Gambit 11) Even though Berkoff sympathized with the actor, as his career developed he directed more than he acted. He began to direct plays and then star in the revivals as he did in Salomé (as Herod) and Coriolanus. This method leads to ethical and creative problems which Berkoff acknowledged in Coriolanus in Deutschland:

Berkoff's Salomé premièred at The Gate Theatre in Dublin before transferring to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. Berkoff did not appear in the original, but remounted the play, casting himself as Herod for what turned out to be a successful run in London. After accusations that Berkoff stole the production -- and his portrayal of Herod -- from the Gate, Berkoff defended his ownership:

Berkoff further defended his method in Free Association, and gave more insight into his directing technique: "This is much how a dance works -- a dancer/choreographer will put another dancer in in order that the choreographer may shape the performance from an eyes-front position, then he or she can step in" (360). These ethical problems associated with Coriolanus and Salomé are the reverse of Berkoff's early career when he originated roles which he later handed to other actors. Since the original production was a vehicle for Berkoff himself, his shadow remained on the character. For a 1984 article, Anne Marie Welsh of The San Diego Union-Tribune asked Berkoff about creative ownership: In Decadence, the detailed mime, the fits and starts and facial expressions, the pinched eyes and simpering mouth, the verbal exuberance, all seem specific to Berkoff. Since he cares so much about casting I ask: "Could he ever imagine that role acted by another?" "Of course I can," Berkoff booms, "that role is very simple to adopt and re-create in your own body. The only people who find acting difficult are bourgeois people. Actually the greater the acting the easier it is to adopt. (E2) In the same article Berkoff reconnects acting to, in his opinion at the time, its supremacy over directing:

By 1998, however, Berkoff re-evaluated his various roles, now leaning toward his identity as a director over actor:

Although Berkoff's perception of himself as an artist has evolved, music has remained an essential element of his production style. He considers sound and music as a way for the actors to develop characters. All of Berkoff's music is composed during the rehearsal process, with musicians present at every rehearsal. He believes that music is a stimulant for the creative process, essential to create "total-theatre."

The music, spurring the imagination, is the one element of every Berkoff production that is created anew. For example, Mark Glentworth created the music for the 1986 British production of Metamorphosis at the Mermaid Theatre in London and Larry Spivac created the music for the 1989 New York production. From Berkoff's distillation that acting is ultimately a "search for self," Berkoff sums up what, he believes, acting, and theatre in general, means. Within the overall context of Berkoff's life, he has constantly been attempting to find himself. All of the components of his acting and directing style -- choreography, improvisation, verbal, physical, environmental -- are part of his search. It is easy to suggest that art is a reflection of the artist; in Berkoff's case, all of the contradictions within the Berkovian aesthetic are a reflection of the man himself.

© Craig Rosen 2000 |