|

home

advanced |

Creating

the "Berkovian" Aesthetic Chapter I Introduction In 1969, Steven Berkoff presented the debut of his adaptation of Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis at the Round House Theatre in London. This production was significant because Berkoff -- serving for the first time as writer/adapter, director, and actor in a full-length project -- presented an aesthetic which would become identified as his artistic trademark. Metamorphosis combined elements of Brechtian Epic Theatre by using actors to purposefully represent characters rather than become them; Antonin Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty by breaking from traditional theatre texts and asking the actors to bare their inner thoughts as if they were human-sacrifices to create ritualistic theatre; Jean-Louis Barrault’s “total-theatre” by using all possible means to uncover the meaning -- conscious or otherwise -- of the play; and Jacques Le Coq’s theories of mime, movement, masks, and ensemble, by using the performers to create the environment. Even though Berkoff appropriated production styles from others and adapted the spoken words from a novel, the end result was uniquely Berkoff's. Berkoff's production of Metamorphosis was an eclectic abstraction of Kafka's tale of a salesman who wakes up to find himself transformed into a beetle. Berkoff, dressed in a period business suit, created his "bug" through a mixture of precisely choreographed mime and movement -- sometimes scurrying on the stage on his fingertips, arms, legs, and belly, and, at other times, hanging from a set composed of metal bars. He combined this movement with a stilted vocal delivery to explore the essence of the role, not the surface. This portrayal was striking in its simplicity and established the writer, director, and actor as a virtuoso artist capable of captivating an audience. Berkoff would revive Metamorphosis nine times over the next twenty years, gaining more notoriety with each production. As Berkoff would do many times in the future with the works of Poe, Wilde, Shakespeare, and others by Kafka, his own production aesthetic -- the performance "text" -- became as powerful and important as the written text. Berkoff and his various critics often refer to his own work as “Berkovian” or “Berkoffian” (Berkoff, Meditations 97; Currant 43; Appleyard 69; Brown, Rev. of Acapulco 15; Jinks n. pag.) suggesting the perception of a very personal and original performance style which Berkoff assumes responsibility for and is credited with developing. Berkoff’s acceptance, to varying degrees, by the commercial, artistic, and critical theatre communities helps to provide criteria for judging his overall importance and success. In Meditation on Metamorphosis (1995) he seems to challenge someone to define this style when he writes, “More than ever I feel my work develop into a kind of school, not by rigid formula but by learning certain techniques which expand your ideology and communication skills” (137). With this in mind, the purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the elements of the “Berkovian” performance/production style; to argue where it fits into a larger critical framework; and, to question whether the “Berkovian” style will flourish after Berkoff is no longer producing theater. For more than thirty years Berkoff has directed and/or performed internationally, including productions in France, Germany, Scotland, Israel, Cyprus, Australia, Japan, the United States, and his native England. He has twice been invited to direct for the New York Shakespeare Festival and has also directed for the Royal National Theatre in London. For these theatre companies, Berkoff has directed various works in his own unique style. Whether the plays were his own, other playwrights', or Berkoff’s adaptations of novels by Kafka or Poe -- he has managed to apply his own performance style to the given dramatic text, proving the Berkovian performance style to be flexible through its adaptability. In addition to directing for some of the most important theatre companies in the world, very prominent artists have performed in various Berkoff productions, rising to the challenge of learning the “Berkovian” acting style. Some of these performers include Roman Polanski, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Irene Worth, Anthony Sher, Tim Roth, and Christopher Walken. Little scholarly research has been conducted on Berkoff to date, and even less attention has been paid to his performance style specifically. Most studies of Berkoff have focused on his original texts and adaptations, while most of the attention directed toward Berkoff's performance style is contained in reviews of his productions. Major Berkovian analysis and criticism can be broken down into three major categories -- playwriting, biography, and autobiography. Given his unique performance style, and the notoriety he has gained, it might be considered odd that there has not been more extensive research conducted regarding Berkoff’s theatre work. This may be largely due to the fact that many of the major works written by Berkoff have been autobiographical. Fortunately, he has written a few journals which chronicle the rehearsal and creative process he has gone through for his various productions. Among these publications is Meditations on Metamorphosis (1995), a journal of Berkoff’s time spent in Japan directing the tenth major production of Metamorphosis, and Coriolanus in Deutschland (1992) which chronicles the rehearsal process for his 1988 production of Coriolanus in Münich, Germany. Berkoff traces the evolution of these productions through the rehearsal process explaining how the pieces came together and how he molded an acting company to work within his aesthetic. At times, in his writing, Berkoff free associates in flashback form to previous productions of Metamorphosis and Coriolanus and describes changes, similarities, and creative differences between productions. Berkoff has also published a production journal, I Am Hamlet (1989), which chronicles his production of Hamlet (1979). The book is set up as an abridged script for his interpretation of the play -- complete with Berkoff’s running commentary on the text. Included is blocking and photographs from his production which opened in Edinburgh and toured throughout Europe for the next two and a half years. The tour finished at the Théâtre du Rond-point, hosted by Jean-Louis Barrault. Another of Berkoff’s books is The Theatre of Steven Berkoff (1992), an archival photo-journal of many of Berkoff’s productions with captions describing each photograph. Berkoff’s intent in writing Meditations on Metamorphosis, The Theatre of Steven Berkoff, and I Am Hamlet is to share insight into his creative process. Berkoff seems to want to explain elements of his production style and the theoretical groundwork behind it. At times, however, these journals appear more autobiographical than theoretical. Other than Berkoff's autobiography, Free Association (1996), there is no "authorized" biography. Free Association includes information about Berkoff’s childhood, early influences, inspirations, and professional experience. The style of the book provides insight into Berkoff’s thought process; the title refers to Berkoff’s style of writing. He writes a few pages at a time about a specific incident, and then shifts focus to another incident in his life in a "free association." Berkoff has given many interviews and written short articles which have been printed in various journals. The most important of these is an article titled “Three Theatre Manifestos” (1978). Here a young Berkoff describes the tenets of his theatre. Some of it sounds remarkably like Artaud: “Acting is for me the closest metaphor to human sacrifice on the stage” (7); other parts echo Brecht: “By describing the accident, the witness becomes the accident; he is there reliving it” (11). Berkoff’s plays have been published in three volumes simply titled Steven Berkoff: Collected Plays, Volumes 1 and 2 (both 1994), and Volume 3 (2000). Although I am specifically focusing on Berkoff’s production style these scripts will be valuable tools used to answer the following questions: Do his plays prescribe a specific acting style? Is a company obligated to the “Berkovian” acting style? How much of Berkoff’s performance text is included in the written text? The only major study of Berkoff’s work to date has been Paul Currant’s 1991 dissertation, The Theatre of Steven Berkoff (not to be confused with the aforementioned photo journal of the same name by Berkoff himself). Currant states that the purpose of his study is to "trace his [Berkoff] career from the 1950s to the 1990s in order to find the essentials of his theatre" (i), his major focus is Berkoff’s plays which he groups according to when they were produced while supplementing his analysis with biographical information. Currant looks at Berkoff’s childhood and early training as an actor, then he divides Berkoff’s canon into three chronological sections. Currant traces an evolution of Berkoff’s themes and writing style while discussing performance style mainly as it applies to a written text. Most of Currant’s performance analysis comes in the penultimate chapter of his dissertation. In this chapter Currant specifically addresses Berkoff’s aesthetic. No other full-length studies of Berkoff have been conducted to date. As noted earlier, there are numerous articles, reviews, and interviews which address Berkoff biographically, as a playwright, a performer, or director. Some also focus on Berkoff’s attitudes or politics. He has been described as “a ferocious satirist” (Prunet 92), “provocative” (Boireau 77), an "enfant terrible" (Mick Brown n.pag.; Currant 1), and “compelling and disturbing” (Townshend www.east-productions.co.uk- link has gone). Other reactions are primarily concerned with the public Berkoff: the celebrity and his attitudes. While these are helpful, they are far removed from an in-depth analysis of his performance style. Other major sources of information pertinent to this study include reviews of Berkoff’s productions. Reviews are readily available from the production of his first original play, East (1977), at the Royal National Theatre, through the present -- including reviews of his work for the New York Shakespeare Festival, Edinburgh Fringe Festival, and his touring productions. These reviews are both descriptive and prescriptive, varying in critical response. Because of his global popularity, as an artist who works in popular venues as well as fringe-festivals, it is difficult to categorize him as a “fringe” artist anymore; but, his work still stirs passionate debate among his fans and critics. In his autobiography Free Association, Berkoff often alludes to different critiques of his production style. Although he shows a sense of contempt for his critics, Berkoff often uses reviews as fuel for his own creative fire. Always needing to prove the value of his own work, Berkoff seems to pay special attention to the notice critics give him.

Berkoff is now over sixty years old and although he continues to work steadily, his thirty-plus year theatre career has covered enough ground to warrant serious analysis. Although Berkoff has become a prominent playwright in his own right, the focus of this dissertation is an analysis of his specific performance style. This analysis pushes Berkovian study to a new arena -- both complementing and exploring Berkoff’s previously published views on performance theory and the existing research concerning Berkoff’s playwriting and biographical history.

Chapter II Biography Steven Berkoff has been a vital force in British theatre since the late-1960s. While much of his generation embraced the image of the rebel with the advent of “kitchen sink drama,” Berkoff personified the “angry young man,” spending time in a detention center, attacking the British class-system, and verbally assaulting his peers in the theatrical establishment while carving out a niche for himself in fringe theatre circles.

He is often perceived as a megalomaniac, though he stresses collaboration between artists and often relies on the unity of a large chorus to realize his specific artistic vision. Berkoff’s rebellious attitude and quick temper are juxtaposed against an idiosyncratic man yearning for acceptance.

Berkoff’s father never joined the family in New York to offer support while Berkoff’s extended family soon tired of housing the family of three. Upon their return to London, the Berks family reunited with the man of the family and was housed by another aunt. Soon after, the family moved into a two-room flat with no toilet and a shared outhouse. During a frigid winter they resorted to a bucket instead of treading outdoors. Berkoff’s strained relationship with his father remained a lifelong issue, which was never fully resolved. In a 1997 radio interview with Anthony Claire, Berkoff describes his father as

In his 1996 autobiography Free Association, Berkoff continually reinforces his tumultuous relationship with his father:

Once settled back in England, Steven spent two years attending a first-rate grammar school, the Raines Foundation, where he was put in the “A” stream. He formed a special bond with his English teacher, Mr. Shivas, who encouraged Berkoff to explore his interest in writing. Two years later, the Berks family moved to subsidized housing in Manor House in the East End of London. Due to the relocation, Berkoff transferred to Hackney Downs Grammar School where, coincidentally, Harold Pinter was completing his own studies. At Hackney Downs, Berkoff was inexplicably sent down to the “C” stream of students, crushing his self-esteem and causing him to lose interest in his studies. In Free Association, Berkoff explains that, “The shock of downgrading was so severe that I never really recovered, since at the age of twelve I had great pride in myself and what I felt to be my goals -- which were to be famous as either a ‘writer,’ ‘a priest’ or ‘film star’” (8). Berkoff’s father, a tailor, discouraged Steven from his own vocation, leaving the young man with little direction and no role model. Berkoff spent summers at the Stamford Hill Boys Club, a club frequented by Jewish boys of exiled families from Eastern Europe. During the summers the boys were taken for a two-week summer camping expedition on The Isle of Wight. In Free Association, Berkoff reports these early feelings of isolation and loneliness:

His strained relationship with his father, his nomadic family life, his downgrading in school, and his lack of close friends led to teenage years spent as a part-time hustler, searching for companionship and a role model. Berkoff’s search was never adequately filled, but, at the age of twelve, Berkoff was employed in his first job: selling Biro pens in a stall for a man nicknamed the “Pen King.” In retrospect Berkoff sees this job -- attempting to draw crowds in order to hock the pens -- as his introduction to show business. “I will never forget the astounding flair and energy of the Pen King,” Berkoff reminisces, “He was my guide into the realms of teasing an audience, and like it or not I was getting a taste from behind the stall of seeing the customers separated from me by a stage” (Free Association 26). Later, Berkoff was hired by a friend to keep lookout for police while selling faux-pearls on the street, an incident which Berkoff he chronicled in West (1983):

In 1952, age fifteen, Berkoff left school at Manor House for a series of dead-end jobs such as an office clerk, messenger boy, and salesman at a Cecil Gee clothing shop. One day, Berkoff stole a bicycle with the intention of fencing it for five pounds but was arrested and sentenced to three months in a detention center for boys. Despite these potentially damaging occurrences, Berkoff acknowledges, in retrospect, sentimentality associated with the memories of his youth:

Berkoff embraced romantic memories of a rough and tumble youth in his plays East (1975), Greek (1980), and West (written 1978; first produced 1983), creating a romantic mythology around youth. In his dissertation The Theatre of Steven Berkoff (1991), Paul Currant notes, “While Berkoff does remember and dramatize the feelings of excitement and vitality of the East London of his youth, he is equally aware of the social inequality, apathy, waste, and loneliness that also permeated that environment” (16). It was the early 1950s, and Berkoff was a rebellious teenager who was exploring different areas of the cultural spectrum as he continuously searched for an identity. He listened to music as diverse as Chopin, Count Basie, and the 1950s crooner Johnnie Ray. He also began thinking about a career as an actor, admiring Marlon Brando, Anthony Quinn, James Cagney, and Jack Palance (Free Association 151). The Hollywood screen “rebel” became the role model that Berkoff was looking for. By the age of sixteen Berkoff was out of school, a detention center alumni, and the veteran of a series of dead-end jobs. Although this period was difficult for Berkoff, he later used it as inspiration for his earliest plays. In East (1975), Berkoff wrote a vitriolic monologue for his semi-autobiographical character, Les, that depicted his experience as a clothing salesman:

Berkoff later saw a help-wanted advertisement for Burberry’s who needed help selling clothes overseas, at outposts located near American army bases. He was hired, and in 1954, at age eighteen, moved to Germany. While in Germany, Berkoff picked up the book that changed his life, “a book by a man with a strange name, Franz Kafka” (Free Association 168). Berkoff describes his initial reaction to Kafka’s Metamorphosis (1912):

For the next few years, Berkoff worked at various shops in Germany and Iceland, but, having worked a plethora of odd jobs from age fifteen to twenty-one, Berkoff never explored the dream of his youth -- the theatre. Upon his return to London, Berkoff found that John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger (1956) was revolutionizing British theatre and popular culture. Berkoff, however, did not identify with Jimmy Porter as he had with Gregor Samsa; the social-realism of Osborne's theatre that served to express much of his generations’ disillusionment alienated Berkoff:

In a 1993 interview with Nick Curtis, Berkoff differentiates himself from the “angry young man” depicted by Osborne. In reference to his “image of the raging, blank-verse bovver-boy,” Berkoff replied, “I’m not angry. John Osborne is angry. I’m Chaplinesque. My hands aren’t for punching, they’re for movement and grace” [Berkoff’s emphasis] (quoted in Curtis 12). Upon his return to London, Berkoff enrolled in theatre classes at City Literary Institute. It was six years since he begrudgingly attended school, and he was now enjoying it immensely. Slowly the bad taste of Hackney Downs faded as Berkoff threw himself into his studies, becoming especially fond of Edmund Kean [Ref 2-2] whom Berkoff describes as “an outsider who felt distinct discomfort with the acting profession and with those who went to genuflect at his feet” (Free Association 215). Berkoff, yet to perform in his first play, was already identifying with a rebellious actor and a Jewish novelist whose themes centered on isolation and alienation. Even though he trained only for three semesters at the City Literary Institute, Berkoff, in 1958, was admitted to the Webber-Douglas Academy of Dramatic Art in London and granted a scholarship with stipend. For the first time in his life, Berkoff opened a bank account and was slowly becoming a more traditional member of society. At Webber-Douglas he studied Friederich Nietszche, Jean-Paul Sartre, Arthur Miller, Brendan Behan, Tennessee Williams, and Joan Littlewood, in addition to various dance, movement, and acting styles. Berkoff found his new education stimulating, but was disheartened by the lack of discipline within the school; he felt that the state money supporting his education was wasted since he found that the academy was run rather shoddily. In the summers of 1958 and 1959, Berkoff found some work as a movie extra in films like The Sheriff of Fractured Jaw, [Ref 2-3] The Captain’s Table, [Ref 2-4] The Devil’s Disciple, [Ref 2-5] and I Was Monty’s Double. [Ref 2-6] Berkoff graduated from Webber-Douglas in 1959, and signed with his first agent, John Penrose. Penrose found Berkoff work: minor film roles and in touring companies, including Rudolfo in Arthur Miller’s A View From the Bridge, which debuted in Bradford before touring to Kettering and Finsbury. Although he was a working actor, Berkoff did not find touring life gratifying, especially in his personal life. As in his youth, loneliness began to set in. “The theatre began to tire me,” Berkoff wrote, “with its routine and the loneliness, since there was no real fraternization, no change of personalities as there is in rep and no demanding work for me to do. I was rotting away with a good salary” (229). The discontented actor arranged to leave the company and continued his training at the Laban School of Dance in Morely College. He also continued to be cast in small roles of shows booked on exhausting tours. 1960s Arthur Kopit's Oh Dad, Poor Dad, Mama's Hung You in the Closet and I'm Feeling So Sad made its British debut at the Arts Theatre in Cambridge in 1961. Berkoff was cast in a small role, but the production was significant as Stella Adler was set to star. Berkoff expressed a surprising respect for the method actress in Free Association:

Unfortunately, the production quickly closed because of friction within the cast and Adler's problems remembering her lines. Berkoff’s next break came in 1962 when director John Dexter was filling cast replacements in a remounted production of Arnold Wesker’s The Kitchen at the Royal Court Theatre. [Ref 2-7] Berkoff never felt comfortable with the cliques that evolved within the Royal Court. In Free Association, Berkoff says of his time with the Royal Court, “Since I was not part of this club nor remotely desired to be, it might be that I suffered some degree of alienation or paranoia, but it was a feeling others shared” (187). In The Kitchen Berkoff played Raymondo, a small role, but he was impressed by and proud of the production, proclaiming it “the first time an English director had succeeded in creating a great physical theatre to compare with Brecht’s” (Free Association 184). Berkoff returned to the City Literary Institute and pursued mime study with Claude Chagrin, who, along with her husband, had been pupils of Jaques Le Coq.

Berkoff was originally cast as The Player Queen and suggested they also cast his friend and room mate Lindsay Kemp [Ref 2-8]. The BBC acted on Berkoff’s suggestion and when Kemp was cast, Berkoff convinced the director, Philip Saville, to allow him to switch roles and play Lucianus. The production was shot on location in Elsinore, providing an opportunity for Berkoff to further his mime work, gain exposure, and observe established actors such as Christopher Plummer as Hamlet, Michael Caine as Horatio, and Donald Sutherland as Fortinbras. Berkoff's major breakthrough occurred in 1965 when he received critical acclaim for his portrayal of Jerry in Edward Albee’s The Zoo Story, directed by David Thompson, at Theatre Royal in Stratford East (one of Joan Littlewood’s former theatres). The Sunday Times anointed Berkoff one of the 1965s top six up-and-coming young actors along with Terence Stamp, Nicol Williamson, Ian McKellan, James Fox, and Peter McEnery. Berkoff considered The Zoo Story to be his big break, thinking that the exceptional press would open doors to the larger theatre companies. Neither Stratford East nor the Royal Shakespeare Company, however, engaged Berkoff so he went to Paris to continue his mime studies with Jaques Le Coq. Work with Le Coq led to a relationship with Jean-Louis Barrault, whose concept of “total theatre” had a profound influence on Berkoff [Ref 2-9]. In his 1991 dissertation The Theatre of Steven Berkoff, Paul Currant sums up this period by saying: By 1965, Berkoff was an established actor in repertory, had seen countless productions, read a great deal, and begun to formulate his central ideas of theatre. His main production ideas were mime oriented, anti-realistic, and (partly) “Artaudian.” Many of the themes and subjects of his subsequent plays -- his Jewish heritage, London, class struggle, Kafka and Poe’s stories -- had also been assimilated. (29) While Currant is correct in this assertion, he overlooks other important points: Berkoff’s thematic preoccupation with loneliness and isolation and his status of “outsider,” which had become firmly planted by this time. Berkoff’s work with established actors, such as Christopher Plummer and Stella Adler, caused him to become an ardent student of acting, theatre history, and world events. Furthermore, Berkoff was exposed to Shakespeare, Brecht, and Artaud, whose work proved to be inspirational. From a young hooligan who spurned schooling emerged a theorist and artist who began knowledgeably rejecting the realism prevalent in his contemporary theatre. He had declined small roles -- partly out of ego and partly out of artistic frustration -- and was now on the verge of creating his own theatre and establishing his name, not just as an actor, but also as a director and playwright. Upon returning to London, in an attempt to avoid the perils of the out-of-work actor, Berkoff tried carpentry and joined the British Museum Library. At the library he stumbled across information regarding a history of anti-Semitism in England, inspiring his first play, Blood Accusation (1966). A reconstruction of elements that lead up to the persecution and trials of Jews of Lincoln in 1290, Blood Accusation signifies Berkoff’s initial attempt to create his own work. He also embraced his Jewish identity, which had been, and continues to be, a key component of his writing. On the day he completed Blood Accusation, Berkoff also jotted down a two person one-act play called Lunch. Lunch was eventually published and performed, debuting in 1983 and directed by Linda Marlowe. Berkoff was cast as Jerry in another production of The Zoo Story in 1966, this time directed by John Warner. He also moved in with the woman who was to become his first wife, Allison Minto. Information regarding Berkoff’s personal affairs is sketchy -- he occasionally mentions his marriages to Ms. Minto and then in the mid-1970s to actor Shelly Lee, which lasted for six years. He doesn’t discuss the reasons for his divorces; since 1984 Berkoff has lived with German pianist Clara Fischer, sometimes referring to her as his wife although they have never been legally wed (Petrou 10). Even in his autobiography, Berkoff, who is so willing to discuss his dysfunctional relationship with his father, keeps his romantic affairs behind closed doors. In a 1999 interview with The Sunday Herald, Berkoff acknowledges:

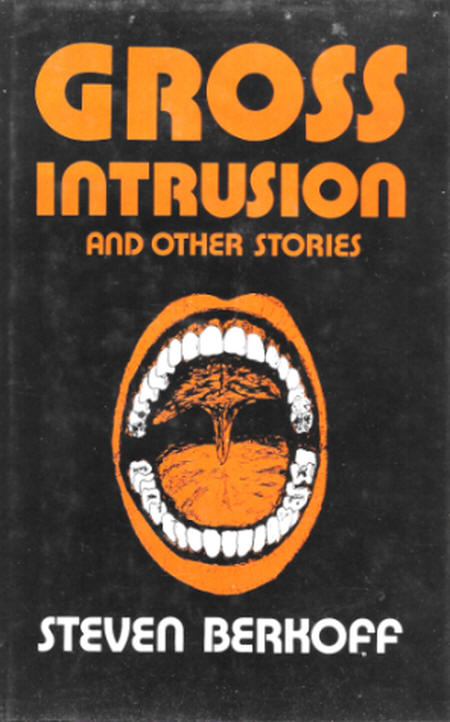

Berkoff suspiciously confirms this information in his 1998 interview with Andis Petrou in the Cyprus Weekly. Asked if he had any children, Berkoff replied: “I’m not sure really. Someone claimed one was mine. They’ve grown up now” (10). Berkoff began writing on a more regular basis, mostly adaptations; his first seven productions were either classics or his own adaptations of short stories. Four adaptations were from Kafka, including: In the Penal Colony (1967) at the Arts Lab in London; Knock at Manor Gate and Metamorphosis (1969) at The Round House; and The Trial (1970) at the Oval House. In the early 1970s, Berkoff directed Macbeth (1970) at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art; and his own adaptations of Aeschylus’ Agamemnon (1971) at The Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and August Strindberg’s Miss Julie (renamed Miss Julie Versus Expressionism in 1972) on tour through Brighton, Glasgow, and Edinburgh.

The excitement of In the Penal Colony inspired Berkoff to debut Metamorphosis (1969). The initial production, with Berkoff directing and playing Gregor, had a limited three-week run at the Round House in London. In Meditations on Metamorphosis, Berkoff notes that this first Metamorphosis “was to be the hallmark of all my future work” (110), because it established Berkoff’s aesthetic and inspired nine major revivals. Berkoff next directed Shakespeare’s Macbeth (1970) in London, gaining experience and assuming full control of his work by producing, directing, and performing the title role. He understood this was the best way of freeing himself of others' commercial restraints and artistic visions, even if it meant that he would have to shoulder the entire financial burden. Berkoff was still a little-known actor, though he was gaining notoriety as a director and performer for his Metamorphosis and Macbeth. 1970s Berkoff continued to perform small movie roles but he quickly became disenchanted with the movie business. After working with a group of hungry stage actors for the previous six months, he found that the film actors had little work ethic. While filming Nicholas and Alexandra (1970), [Ref 2-10] the actors would drink to idle their time away while in Spain and, although they were good-natured, Berkoff found them to be loud and boorish. Berkoff enjoyed Spain but was ready to return to London where he again found it difficult to find stage work. He acknowledged, “I had to get back to doing my own productions, but the wear and tear of casting, directing, producing and finding the few bob with which to do it was as enervating as it was exhilarating” (Free Association 305). He had worked with the same core actors since 1968, and decided it was time to formally form his own company; The London Theatre Group’s first production was Kafka’s The Trial (1970) at the Oval House. [Ref 2-11] In 1972 Berkoff received his first British Arts Council grant which proved to be a mixed blessing. The initial elation of the funding soon turned into the panic of expectation since he was now obligated to produce theatre on demand. He and his group of players -- which included Steve Williams, Terry McGinty, and Tony Meyer -- decided to mount a season which included John Ford’s ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore and a revival of Metamorphosis. ‘Tis Pity was dropped but the group remounted Metamorphosis and coupled it with a Berkoff adaptation of a collection of Kafka’s short stories which they called Knock at the Manor Gate. In a 1977 interview with Sheriden Morley of the Sunday Times, Berkoff remembered the period before his first Arts Council grant in a positive light:

In 1972 Berkoff set to work on Miss Julie versus Expressionism and toured through Northern England and Scotland with a production of The Zoo Story, directed by Berkoff (who cast himself as Jerry). The relationships within the original troupe were becoming strained so they disbanded but Berkoff immediately recast the shows and took them back on the road. After a month-long vacation in the Greek islands, he continued to revive his previous work, this time selecting Agamemnon and The Trial. From 1973 to 1975 Berkoff revived his earlier shows in addition to mounting an adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher (1974). This production marks the end of the early period in Berkoff’s career because in 1975 the London Theatre Group travelled to the Edinburgh Fringe Festival to première Steven Berkoff’s first original play, East. Eventually, East transferred to the Royal National Theatre in London in 1977. East is Berkoff's celebration of misdirected, wasteful youth. Now a full-fledged playwright, Berkoff integrated cockney slang with verse and song, boldly empowering his dialogue. In his introduction to the East, Berkoff explains:

Milton Shulman of The Evening Standard called it "a raucous, bawdy, uninhibited series of sketches that caricatures a way of life that has managed to survive the beguilements of civilization and the pressures of State Education" ("Wondrous Cockneys" 19). There were two major revivals of Metamorphosis in 1976, first at the National Theatre in London and then the Nimrod Theatre in Sydney, Australia. By 1977 Berkoff’s company had an established repertoire and were gaining a reputation throughout Britain. Peter Hall needed to fill in some dark time at the National Theatre and invited The London Theatre Group to perform a three week repertoire of East, The Fall of the House of Usher, and Metamorphosis. The plays sold very well and Berkoff received excellent notices from The Sunday Times, The Financial Times, and most other British publications. Nevertheless, their run was not extended beyond their initial engagement and Berkoff was not invited back to direct at the National Theatre for thirteen years. Berkoff never fully understood why he was not asked back for such a long period, but, in Free Association he suggests professional jealousy:

In 1978 the BBC commissioned Berkoff to write a screenplay. They saw East and believed that Berkoff had potential as a screenwriter. Berkoff accepted the commission even though he was forced into the situation he had been in when he was awarded his British Arts Council grant: to produce a product on demand.

Inspired by East, Berkoff wrote its equally blunt sequel: West. Upon completion Berkoff submitted West to the executives at the BBC who did not know what to do with the confrontational script. The project was shelved until West received its stage première in 1983. [Ref 2-12] Although West was not produced, 1978 did find Berkoff in Haifa, Israel, directing yet another revival of Metamorphosis -- this time, through an interpreter, in Hebrew. In 1978, Berkoff also published “Three Theatre Manifestos” in Gambit magazine in which he explained the Berkovian aesthetic, which, he contends, remains constant to this day (Personal interview). [Ref 2-13]. He also continued his movie work during this period, garnering more accolades when he was nominated for a 1979 British Screen Award for his portrayal of the villain Ronnie Harrison, opposite Roger Daltry [Ref 2-14] in McVicar. Although he did not win the award, Berkoff’s stock was rising as he established his trademark film persona: the villain. Berkoff directed and starred in Hamlet, which premièred at the 1979 Edinburgh Fringe Festival to poor critical and commercial reception -- Nick de Jongh of the Guardian was so caustic that Berkoff, half-jokingly, threatened de Jongh’s life. Nevertheless, the tour of Hamlet to Edinburgh, Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, Israel, and Paris was critically and commercially successful. In 1999, Berkoff returned to Israel to again direct, though not perform, Hamlet.

1980s In the early 1980s Berkoff established himself artistically in Los Angeles while continuing his work in England. After debuting Greek (1980), his East End adaptation of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, in England, Berkoff staged it in Los Angeles in 1982. Berkoff then directed and starred in the British première of Decadence (1981), his only play (as of this writing) to be adapted into a feature film (1993). He also directed a Los Angeles revival of Metamorphosis; thus he had two productions running in Los Angeles simultaneously: Metamorphosis at the Mark Taper Forum and Greek at the Matrix Theatre. In addition to his work in the United States, he sprinted back to London to perform in Decadence. In 1983, he appeared in the James Bond movie Octopussy, [Ref 2-15] and finally staged West in London at the Donmar Warehouse, later filming it for British television. In 1984, Berkoff staged another production of Agamemnon in Los Angeles for the Olympic Arts Festival. During this period Berkoff’s plays were being performed internationally and his movie roles were more substantial. Berkoff was also a mainstay in the avant-garde art scene since his work was performed regularly at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. He received various British Arts Council grants, toured throughout Europe and Israel, and was cast in larger mainstream films including Outland (1981). [Ref 2-16] In the mid-1980s Berkoff’s entry in the United States theatre scene evolved into his most commercially successful years in the movies. His roles in Outland and Octopussy solidified a trend of typecasting Berkoff as villain.

Additionally, he performed in Transmutations (1985), [Ref 2-19] Revolution (1985), [Ref 2-20] with Prince in Under the Cherry Moon (1986), [Ref 2-21] and Absolute Beginners (1986). [Ref 2-22] Even though Berkoff was now working regularly he still felt like an outsider, as depicted in his play Acapulco (1990). Acapulco, set in the Acapulco Plaza Hotel, is based on his experiences shooting Rambo in Mexico. Its protagonist, Steve, is described by Berkoff as “an English actor, taciturn, [and] moody” (Collected Plays II 89). Berkoff confirms that this character is autobiographical in Meditations on Metamorphosis when he writes that Steve “was naturally based on me” (19). The premise focuses on Steve and a group of actors employed on a film being shot in Acapulco. Steve stands alone as a character with any intellect and depth amongst the banality of his fellow bar-flies. Acapulco reflects the writer's literal self-examination, as opposed to the semi-biographical nature of the East End plays. In 1985, Berkoff returned to the London stage with his familiar formula: a revival coupled with a new piece. Berkoff revived The Tell-Tale Heart and performed a one-man play titled Harry’s Christmas (written in 1982). Turning to a personal theme in Harry’s Christmas, he explores the isolation associated with the holiday period. Approaching middle age, Harry is suicidal at the thought of another lonely Christmas. Counting his friends by the few holiday cards he received, the play culminates with Harry’s suicide, his only escape from loneliness. Berkoff’s theme of outsider evolved from the images of youth depicted in his early plays to the loneliness of a middle-class, middle-aged outsider. The alienated and angry youth of his earlier plays rebelled through sex, violence, and vulgarity while the older, middle-class, loner could muster up nothing but suicide. Berkoff adapted Harry’s Christmas for British television, renaming it Silent Night (1985). The continued success of Harry’s Christmas encouraged Berkoff to further develop other one-man shows including One-Man (1993), and Shakespeare’s Villains (1998). Even though Berkoff had a steady circle of actors, designers, and technicians to call upon, he found the one-man show to be a simple, effective, and inexpensive way to mount a live show.

Berkoff’s other theatre work in 1986 included Sink the Belgrano!, of which, Berkoff says, “even by my modest standards was one of the best things I have ever done” (Free Association 373). Belgrano is based on an incident that occurred during the Falkland Island’s War when a British submarine torpedoed a Argentinean passenger ship (the “Belgrano”). Berkoff charged that Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and her cabinet were informed that civilians were aboard the Belgrano and ordered the attack anyway. Berkoff acknowledges that “The play received mixed reviews and some virulent ones from the right-wing press” (Collected Plays I 146). Indeed, in his review, Martin Hoyle of The Financial Times wrote, "Steven Berkoff the writer thuds into monotony and predictability with a desperately unfunny plod through an over-tilled field to which he can add nothing new." But, Hoyle also commented that "Steven Berkoff the director comes up trumps with the well-drilled depiction of a country's war fever and the cold calculation behind it" (21). The same year he played the ultimate villain, Adolph Hitler, in the twelve-part American television mini-series War and Remembrance, attempting to “make this the truest Hitler of all time” (355). Berkoff was able to fund his theatre work with the large salaries he was making from his television and movie roles. Berkoff spent the summer of 1987 filming Prisoner of Rio in Brazil. He later chronicled this experience -- one of the worst of his career -- in his book A Prisoner in Rio (1989). [Ref 2-25] During filming, Berkoff found the script, treatment of the cast, professionalism, and organization to be frustrating -- leaving him completely disillusioned with the film business. Massage and Acapulco were published together in 1987, although neither was produced at the time. Massage, featuring Berkoff in drag, premièred at the 1997 Edinburgh Festival and is meant to expose the carnal obsession of contemporary western society. In it, a middle class house wife -- played by Berkoff -- begins working at a local massage parlour, where a series of clients enter, including her husband. All of the men are played by one actor, Barry Phillips, a Berkoff mainstay, who has continued to work with Berkoff intermittently since Agamemnon (1973). In 1988, Berkoff had his first collection of essays, America, published; in 1994, Overview, a second collection of essays was released. Berkoff also continued his movie work in The Krays (1990). [Ref 2-26] By the late 1980s Berkoff continually worked in many mediums including: stage (as director, playwright, actor, and producer), film, television, and author (production diaries, short stories, and essays). Berkoff successfully fused his experimental theatre style with artistic and commercial success in his 1988 production of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus for the New York Shakespeare Festival (starring Christopher Walken) and a revival of Metamorphosis (starring Roman Polanski) in Paris. Berkoff went on to present Coriolanus in Münich, Germany, with a translated script performed by a German cast; he later chronicled this production in his journal Coriolanus in Deutschland (1992). Unable to resist a tour-de-force role, Berkoff eventually cast himself as Coriolanus in a British revival (1995) at the Mermaid Theatre in London and a subsequent world tour. He arrived on his own terms: directing productions in the Berkovian performance style and working with scripts that were classical, non-traditional, or self-penned. His revivals have basically retained their original production values and aesthetic, remaining within the original concept, scenic, and costume choices. During his time in Paris working on Metamorphosis, Berkoff began dreaming up a stage concept for Oscar Wilde’s Salomé, which premièred at the Gate Theatre in Dublin [Ref 2-27] before moving to the Royal Lyceum Theatre in Edinburgh during the 1989 Edinburgh Festival. Berkoff was then granted a run at the National Theatre because Laurence Olivier -- one of Berkoff’s heroes -- passed away. Olivier’s widow, Joan Plowright, cancelled the production she was rehearsing, leaving the National Theatre with a gap in its schedule. He again directed and, this time, played Herod; later, in the 1990s, he would take his Salomé on a world tour, playing 235 performances everywhere from Japan to Israel, highlighted by a New York production at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Salomé epitomized the Berkovian presentational style: mimed movement, organically conceived music, and exaggerated use of language. In 1989, Berkoff travelled to the United States to direct his ninth major revival of Metamorphosis. This production starred Mikhail Baryshnikov as Gregor and René Auberjonois as Mr. Samsa. They rehearsed and then debuted this production at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, before moving to New York for a limited Broadway run. 1990s In 1990 Berkoff began to organize his notes for his autobiography Free Association (1996), and prepared a revival of The Trial starring Anthony Sher for the Royal National Theatre in London, which opened in February 1991, playing 50 performances to 30,000 patrons. Acapulco was finally performed in Los Angeles in 1990 and then London in 1992. Acapulco differs greatly from the typical Berkovian performance style. Berkoff instructs: “The acting should be easy and casual broken up by laughter and the normal behavior patterns of people relaxing after work” (40). This naturalistic stage direction is unusual and unexpected for Berkoff, and was noticed by critics. The Evening Standard’s drama critic Michael Arditti panned the show, agreeing with most other critics, saying: His style has undergone a major transformation, moving from the rhetorical to the conversational, without pausing at the dramatic on the way. The virtuoso verse and mime have been replaced by the bar-room babble which, while no doubt authentic, sounds slight.(7) Berkoff’s The Theatre of Steven Berkoff (1992), a pictorial account of Berkoff’s productions, consisting mainly of black and white photos documenting the Berkovian aesthetic, was published. That same year Berkoff also enlisted members of The London Theatre Group to record Macbeth, with himself again playing the title role, this time for BBC Radio and released as a Penguin Audio Book in 1994. Berkoff also has recorded Metamorphosis (1997) for audio release; this is a reading of Kafka’s novel -- not Berkoff’s dramatized adaptation. In the summer of 1994 Berkoff was back in New York directing The Tragedy of Richard II for the New York Shakespeare Festival. Richard II is unique in that it is one of the few productions Berkoff has never revived; Berkoff has never stated the reason for this aberration. [Ref 2-28] In my 1997 interview, Berkoff expressed particular pride in this production:

Berkoff's original plays were published by Faber and Faber in two volumes in 1994. Now a recognizable figure in the British theatre scene, Berkoff continued to mount smaller productions and played diverse venues such as high school gymnasiums and various fringe festivals. In the fall Berkoff returned to London to direct and perform in an evening of two original plays, Sturm und Drang and Brighton Beach Scumbags. Although the title Brighton Beach Scumbags is a reference to Neil Simon’s Brighton Beach Memoirs (1981), the play itself is not a specific parody. As was the case with Acapulco and would be the case through the 1990s, critics rejected these Berkoff originals. The Times’ reviewer Benedict Nightingale stated that Sturm und Drang “is the sort of piece that makes counting the hairs in your eyebrows seem stimulating by comparison” (“Vultures of the Yob Culture” Features n. pag.) and Alistair Macaulay of The Financial Times summed up the evening by commenting, “If a thing is worth doing, Berkoff seems to be saying, it is worth doing noisily, strenuously and frequently” (“The Bile of Berkoff” XIII). Berkoff revived Coriolanus at the Mermaid Theatre and toured throughout the summer of 1997. Almost sixty years old, he committed to a schedule of performing three different plays (Coriolanus, One Man, and Massage) in touring rotation. Between May 1997 and August 1997 Berkoff played one of these three plays in Edinburgh, Jerusalem, Tokyo, Grahamstown and Cape Town, South Africa, Liverpool, and Tampere, Finland. One Man is a three part, one-man show which features a revival of Berkoff’s adaptation of A Tell-Tale Heart plus two short one-act plays: The Dog (1993), and The Actor (1994).

The Edinburgh Fringe Festival presented Berkoff with a Total Lifetime Achievement Award in 1997. By then he had learned to walk a fine line and remained welcome by those on the fringe even though mainstream critics and audiences accepted him as a prominent director. It should be noted that other than Shakespeare, Berkoff, author of 23 plays and adaptations, is the most produced playwright at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival (McGlone, "Now, All the Rage" 2; Cook, "Muse" 10). Berkoff returned to Shakespeare in 1998, performing an evening of Shakespeare’s monologues called Shakespeare’s Villains. Berkoff wove together monologues and soliloquies spoken by Iago, Richard III, Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, Hamlet, Gertrude and Polonius, Coriolanus, Shylock, and Oberon to create a production narrative that is partially stand-up comedy and partially university lecture. Berkoff also conducted a seminar focused on performing physical theatre in the summer of 1998, while also releasing a new short novel -- about a struggling actor -- entitled Graft. He toured Villains through 2000, when not doing other, more substantial, work. Berkoff’s status of outsider, though tenuous by the end of 1990s, is an identity that he clings too. In his article “Blood, Sweat and Berkoff” for the Sidney Morning Herald (1996), Steven Dunne notes: Berkoff got to the top -- now one of the most famous actor/directors in the English-speaking world -- on sheer, hard-worked talent, with a bit of luck and some assiduous timing. He fiercely defends his outsider status: not so much out of the mainstream anymore, but away from the government-subsidized companies in the UK. (n. pag.) Dunne's claim should be questioned, considering Berkoff has continued to accept British Arts Council grants. Berkoff has regularly complained of his lack of opportunities to work at the Royal National Theatre, even though he has directed there three times. In 1997 -- now 60 -- Berkoff continued his attempts to shock, performing Massage in drag at The Edinburgh Fringe Festival. A critical failure, The Telegraph and The Times considered Massage a gratuitous display of vulgarity. Berkoff directed the first major British revival of East in 1999 and rewrote a never produced original play -- The Murder of Jesus Christ (1978) -- renaming it Messiah (2000) for the 2000 Edinburgh Fringe Festival. [Ref 2-33] That same year, Messiah was published in a third collection of plays, along with Berkoff's new adaptation of Oedipus and the completed Blood Accusation, now titled Ritual in Blood. Later in 2000, he published Richard II in New York, a production journal chronicling his experience with the New York Shakespeare Festival and he has planned to publish a new collection of essays. Berkoff has remained an enigma: a known mainstream theatre artist who continuously rebels against the mainstream; and someone yearning for affection as he spurns those willing to provide this affection. In The Times, Michael Church writes: I come in on the tail-end of a furious tirade to his assistant about an interviewer who has dared to opine that he can’t handle human contact, and that it must be horrible to be Berkoff. “That’s insane, I adore affection. I’m a very affectionate person. Like most writers, I struggle with demons and all my work is about loneliness, but I still think I’m incredibly lucky to be me. But if it was horrible to be me, what an ugly thing to say!” [Church's emphasis] (“Mr. Nasty Craves Affection” 6) Berkoff’s personal demons of his youth continue to haunt him. His complexity revolves around the paradox of a desire to be accepted yet consistently spurning this acceptance. His heralded 1999 production of East, coupled with his reworking of earlier texts (Messiah and Massage), has brought him full-circle from a struggling actor to fringe performer to movie star to director at the National Theatre. Now, a recognizable name, he is returning to his roots to reinterpret his early work while embracing his original identity as outsider and basking in the light of critical acceptance. © Craig Rosen 2000 |

Berkoff spent an

increasing amount of time in Los Angeles and, in 1986,

directed the world première of Kvetch

Berkoff spent an

increasing amount of time in Los Angeles and, in 1986,

directed the world première of Kvetch